Disaggregated Storage - a brief introduction

I worked on building disaggregated storage on top of SQLite. All the recent database offerings are built on top of storage disaggregation: Amazon Aurora (the most famous one), Neon, Snowflake, TiDB, etc. This post is my attempt at explaining disaggregated storage in the context of database systems.

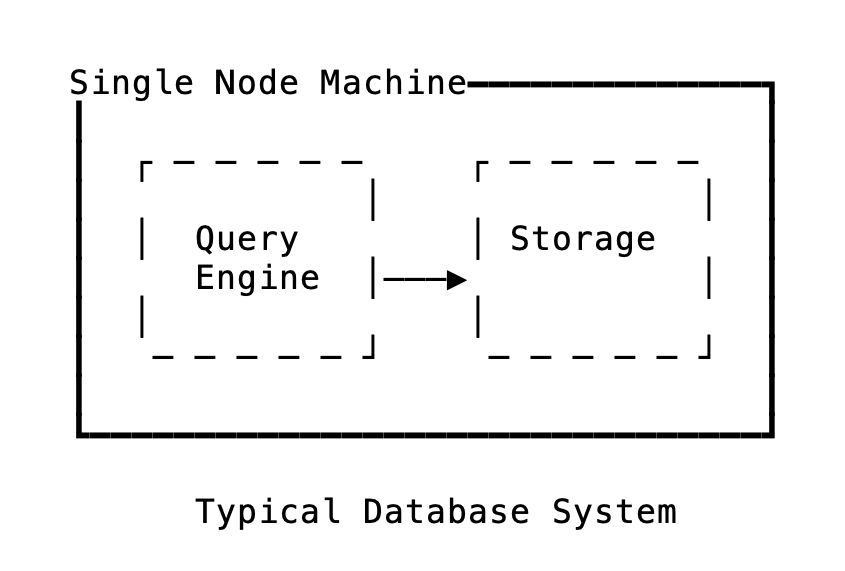

We can break down a database system into two main components: the frontend and backend. The frontend is responsible for handling connections, parsing requests, and query analysis. The backend serves as the storage layer which fetches data from the disk. While the frontend is CPU-heavy, the backend is I/O-heavy.

Popular databases like PostgreSQL, SQLite, and MySQL all have a similar frontend and backend architecture. The data on disk is stored in a B-Tree (or similar structure). The query layer determines which page to retrieve and issues a request to the storage layer like get_page(page_no=13). (In this context, I/O always refers to disk I/O.)

You might have run PostgreSQL locally for development. The database assumes all data is available on the disk, and the frontend and backend are tied to the machine it’s running on. Your database is limited by your disk space – you cannot run a 1TB database on a machine with a 100GB disk. Since the disk is always attached, you cannot just spawn a new node. All the data needs to be copied, which for databases in terabytes and petabytes would take ages for a new node to become active. This affects failover and adding a new node when you have hit the limits of vertical scaling.

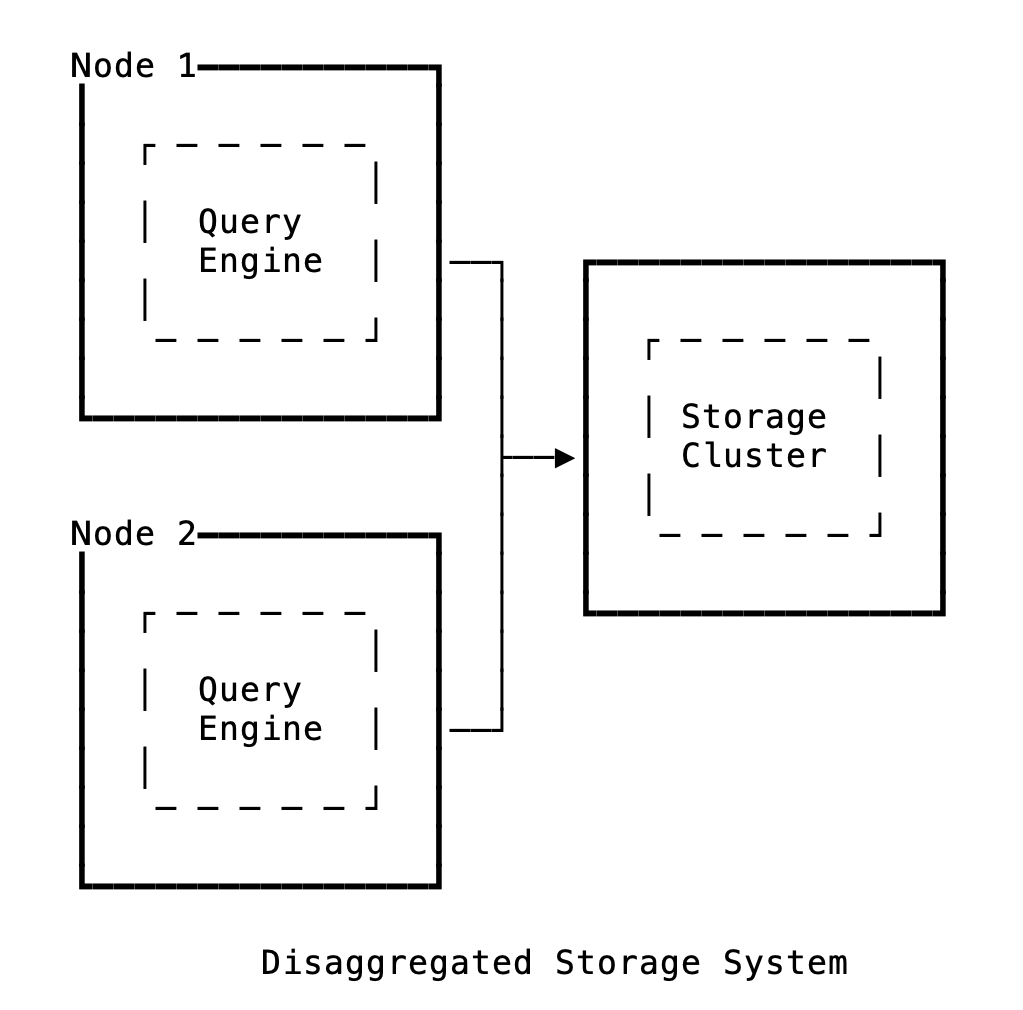

What if we separate them, by storing the data in a separate machine? What if, instead of disk I/O, we do network I/O and bring the data from elsewhere, on demand? Suddenly, your disk won’t be a limiting factor anymore!

This is called the separation of compute and storage, also known as storage disaggregation. You typically store the B-Tree pages in a storage server and get_page is now an RPC call. (Neon calls this method as GetPage@LSN)

Since the disk is no longer attached, it’s easy to scale and scale separately. You can scale CPU and I/O resources independently, and vertical scaling limits won’t matter anymore. You can spawn as many compute machines as needed. Startup and shutdown is instant (hello, Serverless). If your machine crashes, you can spawn a new one without downloading all the database files. Database failover is instant, and you get time travel / Point In Time Restore seamlessly.

But all this comes at a cost: Latency. Disk I/O is way faster than network I/O. Also, while disk I/O operations rarely fail, network I/O calls can fail more frequently.

You might end up doing more network I/O than required. Say your query reads 10 pages but returns only one to the client. To make matters worse, assume the compute layer can read only one page at a time – only after reading a page can it decide whether to read the next one or not. In a traditional model, it’s just 10 disk I/O operations. With storage and compute separated, it will be 10 network I/O operations plus 10 disk I/O operations. Each network call can be expensive in terms of latency!

Most importantly, you need a solid storage server: strongly consistent, fault-tolerant, and horizontally scalable. Compute machines are stateless – they can crash and burn without consequence. But the storage server needs to be fault-tolerant. With the traditional model, all data is on disk, so if that machine crashes, only that database will be down.

If the storage server crashes, the entire fleet of databases will be down. Also, how do we horizontally scale the storage server? Well, that’s a problem for another day!

Thanks to Mr. Aku for reading an early draft of this and bouncing off ideas.

1. Another alternative is a system like Vitess, which enables horizontal scaling by intelligent sharding and connection management.

2. Latency issues in disaggregated storage can be mitigated by caching (at reads) and batching (at writes).

3. There are tricks people do, like predicate pushdown to reduce the amount of read and network latency.

4. Due to operational complexity and trade-offs, disaggregated storage makes sense primarily for database vendors and large tech companies, rather than organizations running just a few databases.